If you’re about to criticize me for only providing the slides in light mode, switch your computer to dark mode. If you’re confused by why the slides are dark blue instead of white, switch your computer to light mode.

This presentation will revolve around answering two important questions: what are conlangs, and why do people make them?

What are conlangs? Conlangs are one of the two classes of languages.

Natural languages are those like English, Chinese, Swahili, and Tok Pisin. These are formed when people speak normally and naturally evolve through the linguistic processes of change. Today, we have thousands of natural languages because groups of people split up and their languages diverged through continuous evolution.

Constructed languages are those like toki pona, Esperanto, Dothraki, Ithkuil, Viossa, Toaq, and Lojban. These exist because somebody decided to create their own language with intention. Many constructed languages are intended to be spoken by humans, but certainly not all. While constructed languages often don’t have many native speakers, they are still real languages.

These two are often called natlangs and conlangs respectively.

Many conlangs have been created over the years, with one very old one we we have direct evidence for being Lingua Ignota. Lingua Ignota was created in the 12th century by the nun Hildegard von Bingen as a way to connect more deeply with God. Its vocabulary drew primarily from Latin.

Hildegard cited divine inspiration for their language, and it thus fits into a subcategory of conlangs primarily used for spiritual purposes.

Many other languages have been created their own languages since then, with a massive explosion in the 20th and 21st centuries. Many recent movies have hired professional conlangers, who have made Klingon for Star Trek, Na’vi for Avatar, and Dothraki for Game of Thrones, among others.

Why do people make conlangs? There are many reasons, but they largely fall into five categories: to unite the world under a common language, to make a work of media more complete, to provide a medium for artwork, to test the limits of language, and simply because there’s no reason not to.

We’ll look at one example of each.

The most well-known conlang is probably Esperanto.

Esperanto was created in 1887 by Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof as an international auxiliary language, a language which everybody would learn in addition to their native tongue. The idea was to simplify cross-linguistic communication by simply ensuring that everybody spoke Esperanto.

Esperanto was created as an “easy” language by having its grammar be dramatically reduced from that of other European languages, and its vocabulary was said to come from many different sources, so that everybody would have some familiarity with its words before having any Esperanto exposure.

However, Zamenhof’s sources were all primarily European languages, and the sounds came from his mother tongue, Polish. As such, the grammar can be very difficult for speakers of non-European languages, such as over half of the world. As tangible examples, Esperanto includes three tenses (which are not mandatory in Chinese), two cases (which are not mandatory in English), and singular-plural distinctions (which are not mandatory in Japanese).

Esperanto has experienced many criticisms since its inception, and its status as a possible world language has been entirely usurped by English. However, it still is the only conlang with confirmed native speakers (estimated in the thousands), and, according to some estimates, has millions of non-native speakers. The sheer quantity of Esperanto speakers makes it an important language to know about, despite all the critics.

Lojban /loʒban/, created in 1987 by the Logical Language Group, is famous as one of the first logical languages.

Lojban tried to apply a precise logic to how grammatical structures are “filled in”. Each content word (noun/verb amalgamation) has multiple slots, which can be filled in by other nouns to make a complete sentence. This gives Lojban its classic “x1 does x2 in the presence of x3 with instrument x4 after x5” definitions, to avoid introducing prepositions into the language.

Lojban’s name is a compound of “logji” and “bangu”, meaning “logic” and “language” respectively, since its goal is to formalize language.

Another notable loglang is Toaq, but I don’t have a slide for it.

Dothraki is another well-known conlang. It was created in 2009 by David J. Peterson as part of the TV series Game of Thrones.

It was built off of the few phrases found in Game of Thrones’s source series, A Song of Ice and Fire, originally written by George R. R. Martin.

Because it was created for a TV show, Dothraki had some constraints. First, it had to be pronouncable for native English speakers, the show’s primary actors, and so Dothraki does not have as unique a phonology (sound system) as some other languages. However, the ways in which its sounds are combined with the few non-English sounds makes it sound highly foreign to English natives, perfect for a TV show portraying a different world.

Dothraki has since become well-known in the conlanging community, and even has a book created by DJP which teaches it. The book’s cover is pictured here.

Dothraki is part of a category known as artlangs: languages created for artistic purposes.

Tshevu /tsεβu/, created in 2020 by koallary, is semi-famous for its beautiful non-linear writing system.

Instead of the standard rows of text, Tshevu’s primary writing system, Koiwrit, is drawn using stylistic ripples on koi fish. The different rings of a ripple indicate different letters, the position of the ripple overall on a fish indicates its grammatical function in the sentence, and ripples outside of the fish convey additional information.

The art shown here is a recipe in Tshevu. The cover image of this slide deck was also a picture of Tshevu script.

Tshevu, like Dothraki, is an artlang.

Seraphim, created in 2022 by Babelingua for the Cursed Conlang Circus 1, is an example of a cursed conlang.

While it calls itself an “angelic conlang”, since it’s designed to be spoken by biblically accurate angels, Seraphim includes many features which harm its practical usability. A speaker must possess seven mouths to properly enunciate it, pronunciation can involve time travel, and words must be carefully crafted to simultaneously be Hebrew prayers and Seraphim phrases.

Another notable cursed conlang is kay(f)bop(t), but I don’t have a slide for it.

Ithkuil is the ever-present example of a conlang created to test language.

It was originally created in 2004 by John Quijada, and has a reputation as being the most difficult language to learn. This is primarily due to that Ithkuil stacks many grammatical categories into single words, and that there is no language on Earth which has all the same categories as Ithkuil.

Ithkuil has undergone three major revisions since its initial debut. In the fourth and easiest version, it inflects for a minimum of 22 categories on each of its primary nominal words, with only two or three having English equivalents.

(These are concatenation, stem, version, root, function, specification, context, affiliation, configuration, extension, perspective, essence, case-scope/mood, valence/phase/effect/aspect, case/illocution/validation, and word category, respectively.)

Ithkuil uses its expansive grammar to do away with a large lexicon, and thus only has around 6000 roots and 400 affixes. Even its native name, “malëuţřait”, literally means “this feedback-driven/self-sustaining system based on linguistic utterances for communication”, or “this language” in simple English. Because why include a word for “language” when you can derive it yourself?

Due to its systematic derivations, Ithkuil is considered a loglang, a logical language.

One neat thing about Ithkuil is that even though the grammar is complicated, it is almost perfectly regular. Thus, the entirety of Ithkuil’s conjugations and modifiers can be written on a single sheet of paper. All the reader needs to know is the meaning of each abbreviation and the order to put these strings together in a word. And that’s definitely possible /serious!

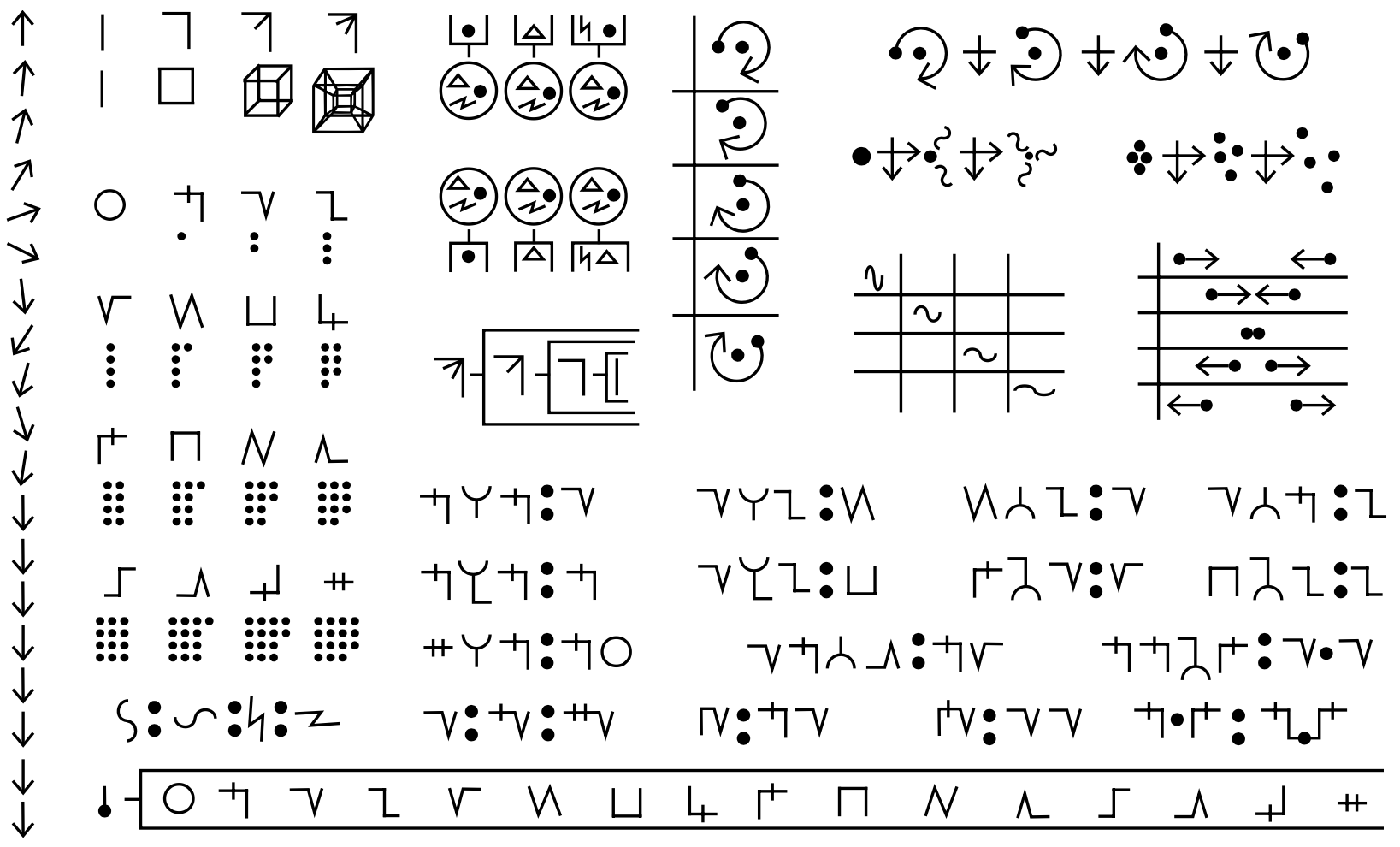

Ithkuil also has a very beautiful and logical writing system. Its writing system is quite different from how spoken Ithkuil works, though, and so many analyze the two as related, but different languages.

As one tangible difference, spoken Ithkuil can differentiate between 9 types of names, but written Ithkuil can differentiate between 22 types of names.

Written Ithkuil is also somewhat more logical than spoken Ithkuil. While spoken Ithkuil has to make concessions so that it is efficiently pronounceable, increasing the spoken language’s irregularities, written Ithkuil has zero irregularities. Everything is in perfect order.

Bonus example! toki pona is one of my favorite languages, and it’s renowned for being one of the simplest and most approachable languages.

Created in 2001 by Canadian linguist Sonja Lang, toki pona is a minimalist language with only around 130 words and a very simple grammar. It accomplishes this by having words which talk about very generic concepts, like “liquid” as opposed to “acid” or “orange juice made using yellow 3 dye”.

toki pona is a great first second language, in that it’s a great gateway drug into learning other languages. I originally learned toki pona because I thought it would be easy, and that experience opened me up to learning two and two halves more languges since!

toki pona also has its own writing system which uses easily-recognizable pictographs for its words, such that one icon represents one word. The picture on the right here is an array of rotated and colored icons, although they are normally written left-to-right, top-to-bottom, perfectly straight, just like English.

If you’d like to learn more about toki pona, come to toki pona club, hosted on Wednesdays in <room>!

Have any audience members made conlangs? If so, feel free to share about them now!

This would be an incomplete presentation about conlangs without explaining the wonderful Cursed Conlang Circus. Hosted by Agma Schwa, also known as /ŋə/, each year for the past three years, the CCC is a contest where anybody who wants to may submit their own cursed constructed language. Languages are considered “cursed” when some aspect of the language is highly unnatural or unusual.

So many wonderful limit-testing and why-not languages have been created for the CCC, including three shown on-screen here, and countless others. If you’ve seen a video on YouTube about a strange language, chances are it was made for the Cursed Conlang Circus.

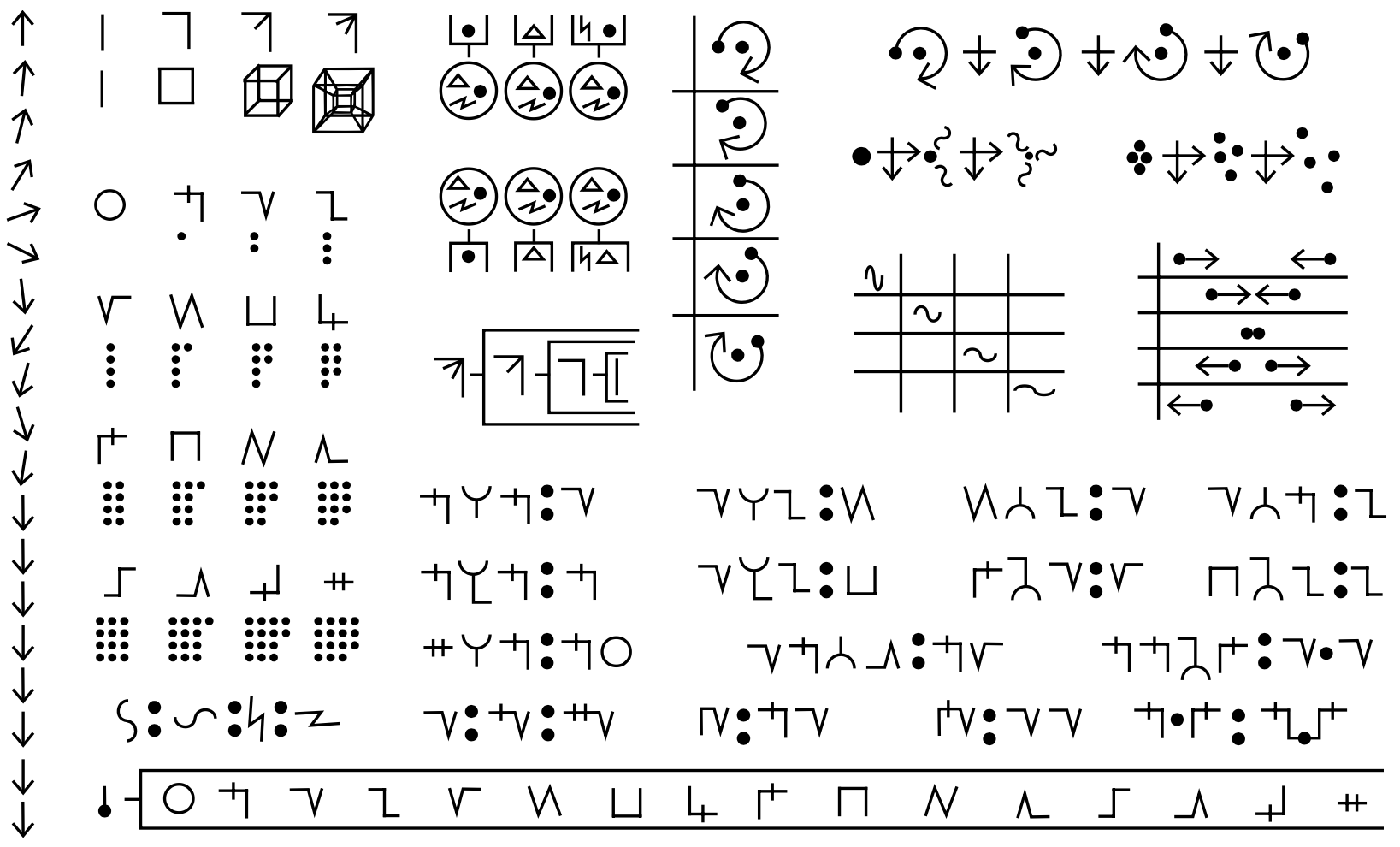

To finish off today’s presentation, we’ll talk about one final practical conlang. Uscript, short for “universal script”, is a language which is meant to use mathematics and logic to be self-defining. In short, one can theoretically learn Uscript just by studying its source text, provided they have some background in mathematics, programming, and physics.

Uscript could theoretically be used on something like the Voyager spacecraft, where the goal is to communicate with another species who may have vastly different knowledge than us. Since it does not depend on human constructs (mathematics and physics are the same everywhere in the universe), it is a great way to communicate with far-away worlds.

A section of the first page of Uscript’s source text is provided here. It is one of the easier parts of the Uscript source to understand, and does not require any background in programming, physics, or advanced mathematics.

I leave it here as a challenge for anybody who wants to decipher it. And while there are no rules for Uscript, that is, you may discuss it with others, I’d encourage you not to give a friend all the answers, especially if they’re trying to learn it themselves.

Questions?